This is the paper I’ll present tomorrow at MLA in Boston. You can see my slides here.

Sovereignty and Sustainability: The Boston Children’s Museum as Native Literary Hub

Today I’ll be discussing an unlikely but powerful hub of local Native literary production: the Boston Children’s Museum. Children’s museums and “children’s literature” shelves can infantilize Native culture and Native people—or worse!; but between the 1970s and about 2000, the BCM empowered local Native people as consultants, interpreters, curators, and writers. When I say empowered I mean paid: the BCM paid Wampanoag, Narragansett and other people to serve on a Native American Advisory Board (possibly the first of its kind), to participate in an internship program that taught them about museum business while bringing them into the space of the museum as interpreters and co-curators, and to write copy for its exhibits and educational kits. Under the auspices of the BCM, Native writers produced a slate of interesting children’s books, anti-colonial historical essays, and manifestoes. Though this program’s heyday seems to have passed, unfortunately, many of the participants continue to write autoethnographies, newspaper columns, traditional stories and other materials.

It’s the appearance of these tightly concentrated bursts of regional literary production that interests me today. Some of you know that I recently finished compiling a large anthology of New England Native literature. [The University of Nebraska Press says that this book will be out in Spring of 2014—it’s been a long time coming, and it’s big: 600 manuscript pages.] In the course of putting all that together I have become intrigued by these windows of opportunity that seem to arise for regional Native authors, especially in the 20th century, both before and after the so-called Native American Renaissance. I like one model proposed by Renya Ramirez, if you know her book Native Hubs: a hub is a place (like an urban Indian center, a school, a powwow arena) where Native people congregate, exchange knowledge, learn new skills (including activist tools), and can bring these back to their home communities. The point of a hub is that it is a center among a number of disparate and far-flung communities, and that people travel back and forth between the hub and their homes. I find this an appealing way of thinking about Native travel, communication and community building; and I’ve been realizing (slowly) that hubs aren’t just spatial: they have temporal and political dimensions, too. In New England, we might say that Native authors have been fostered and promoted by a series of hubs (tribal newspapers and newsletters; tribal museums; a small handful of university programs; and, of course, publishers like the Greenfield Review Press, founded by Marge’s brother Joe and his wife Carol). We might say, moreover, that some of these hubs have a trajectory that closely parallels the rise and fall of local self-determination movements. Some hubs were formed, specifically, in tribal communities galvanizing around federal recognition. And some, unfortunately, have been subsequently weakened under neoliberal policies and economics. (At the end of this paper, I have some questions for you all about sustainability in Native writing and publishing.)

The Boston Children’s Museum, in the last decades of the 20th century, provided one of these hubs. The Museum is a beloved and recognizable feature of the Boston landscape, especially since 1979, when it moved downtown to the waterfront, next door to the giant Hood Milk bottle. It is the second oldest children’s museum in the country (Brooklyn was founded in 1899, Boston in 1913). The BCM started (in Jamaica Plain) as a small two-room enterprise, mainly for science teaching: they kept sample species (flowers, birds, minerals), books and other materials that they could send out to schools on request, and they could also train teachers. The museum underwent something of a transformation in the 1960s, when Michael Spock became the director. Son of Benjamin, Michael Spock is called “the father of the children’s museum movement,” and he brought a particular vision of children’s museums: that they should be “for someone” rather than “about something”—that they should be hands-on, interactive spaces where children could feel “in control” of their environment.

Well may you ask: “which children?” In the 1960s and into the early 70s, the BCM was like a lot of museums in making a point of diversity and inclusiveness. This is still one of their selling points: they have built connections to local African-American activists around issues like school desegregation and science literacy; they have a full Japanese house, donated by the city of Kyoto. But, in the 1960s, at least, they also had Native human remains, and they displayed them, as part of an exhibit called “What’s Inside?” (this had things like a cut-in-half baseball, a see-through telephone, a cross-section of a city street with a manhole kids could climb down. . .and, a “real Indian burial”). The museum also had non-Native staff who re-enacted religious ceremonies using sacred objects like Kwatsi (or Kachina masks).

One of those interpreters, Joan Lester, got the shock of her life when she enrolled in a class at the Harvard Graduate School of Education with 14 Native American students and section leaders, who basically reamed her out for the way the BCM was handling American Indian history and material culture. Joan and Michael Spock have written about this experience, in a couple of brutally honest essays: Joan went back to Spock, told him they were doing “everything wrong,” and Spock said, “Fix it.” So the timing was good for an alliance between local Native activists and some allies who had access to some institutional power. It was a time that Karen Coody Cooper (Cherokee museum scholar) has documented in her book Spirited Encounters, a fascinating history of Native American protest against museums from the 1970s onward. Across the country, and indeed globally, indigenous people started calling museums and other cultural institutions to task for their unethical displays of human remains and sacred items, their hoarding of Native material culture, and for their contributions to mythologies about “national heroes” like Columbus or the Pilgrims.

The BCM did several immediate repatriations and reburials (this was pre-NAGPRA), and formed a Native American advisory board. But the exciting shift, from the POV of literary production, came in 1973 when they were approached by a business called American Science and Engineering, which wanted to republish one of their earlier Algonquian educational “kits.” The BCM said no, but you can pay Native people to help develop a new one, and you have to give Native people complete veto power over the content. AS&E agreed, and the BCM’s published its first Native American writing. Now, with only 15 minutes, we are not licensed for exegesis, but I want to point out just a couple of things. It put in the hands of teachers and children large cards with personalized accounts of contemporary Wampanoag life—these also came with photographs of the artists and writers: this is Gladys Widdis, who was well known on Aquinnah (Martha’s Vineyard) for her stunning pottery made from the clay there. Some of them are fairly radical: Cynthia Akins, inviting kids to think about what it’s like to have a place that you played in and felt was home gradually siphoned off—showing kids that colonization proceeds apace. And it also invited kids into museology, asking them to think about how they would represent contemporary Wampanoag life.

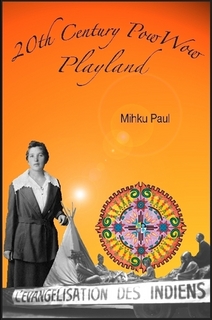

You get the idea: the Boston Children’s Museum shifted dramatically from presenting Indians as dead and gone to engaging children with living indigenous people, and in so doing, it also enabled some interesting writing. Some of the interns produced children’s books as part of their work at BCM (Linda Coombs, who has also done a TON of writing for BCM and Plimoth Plantation—another story); at least one has since collected and self-published her work, which included newspaper columns, recipes, histories.

I need to wrap up soon, but I am interested in researching the circulation of these texts—it should be possible to find out where they were sent out, and possibly whether kids (Native and non-Native) wrote or created anything in response? At the textual level, I see these pieces as both enabled and constrained by a trope of “we’re still here.” If there is one overarching trope in New England Native American writing, that’s the one. “We’re Still Here” was in fact the title of the BCM’s first exhibit co-curated with regional Native people; then the title of a book; it is frequently invoked in regional Native-authored texts. But “we’re still here” has limits. I have been reading the provocative work of John Marsh, who writes about representations of poverty in American literature—particularly about what he calls the “nearly ubiquitous literary convention” of epistemological realism: “the poor really exist! And if [pick your author: Jacob Riis or Rebecca Harding Davis] just exposes poverty, people will do something about it!” But, Marsh says:

if you have to be reminded about poverty as frequently as Americans have needed to be reminded about poverty over the last two centuries, it is not because you are ignorant, innocent, or forgetful, but because you just don’t care. One more poverty-unveiled novel-or a whole class of them-will not likely change that indifference.

Insert “Indians” in place of “poverty”: “If you have to be told that Indians are still here as often as New Englanders (and others) have had to be told that Indians are still here, it might not be just ignorance; it might not even be that you don’t care, but that—as historian Jean O’Brien and others have shown—you actually wish Indians would really go away. In this vein, then, maybe we should not be surprised that “Native hubs” like the one at the Boston Children’s Museum have been among the predictable first victims of new economic austerity measures; the Museum no longer employs Native staff, the internship program is over, its children’s books are out of print, and a fantastic new curriculum tracing Native persistence through the centuries never got finished at all.

So I leave you with the question of what makes a Native hub (a literary Native hub) sustainable? Joe Bruchac seems to have managed partly by his own herculean effort, partly by adapting to new technologies: his Bowman Books imprint now uses lulu.com to publish new chapbooks and re-publish older Wabanaki texts at very low cost. Is it okay, or inevitable, that most other hubs come and go? What exactly can digital media offer here? Is it too heretical to ask whether small runs of paper books may have outlived their usefulness when it comes to circulating and disseminating Native stories, especially stories about indigenous modernity, sustainability and survivance? Does #idlenomore herald a new kind of hub, and what can we learn from it?